First-Person Singular: A Letter to My Fellow Black Chefs

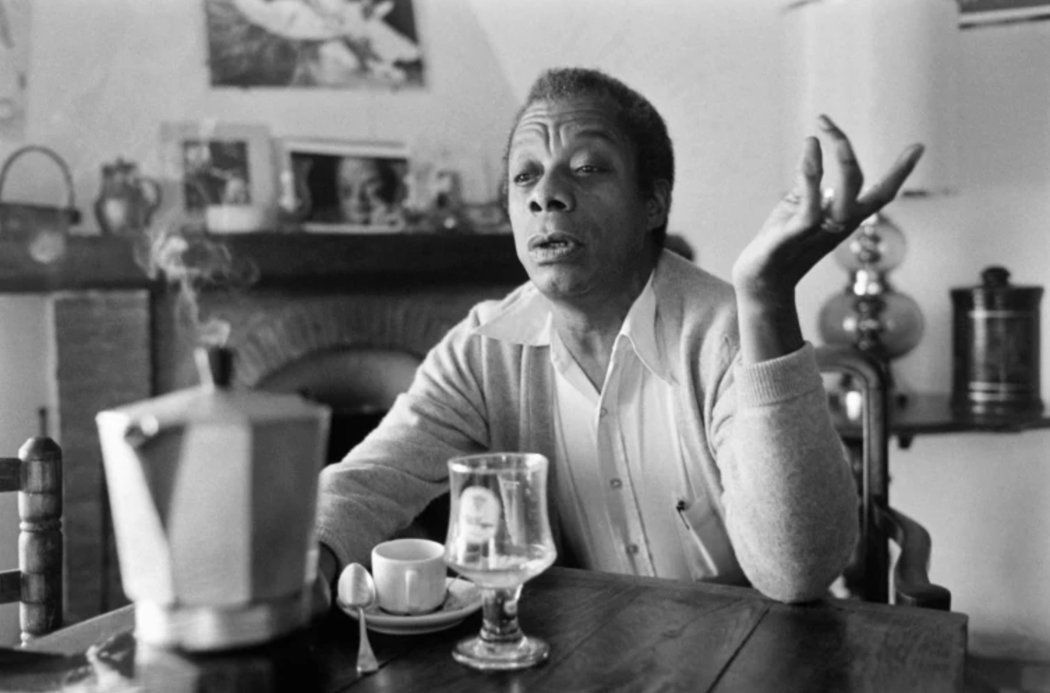

In 1962, my great-uncle James Baldwin wrote an essay to my father to help him navigate through a toxic and racist country. It inspired me to write my own to fellow Black chefs.

In 1962, my great-uncle James Baldwin wrote an essay published in The Progressive titled, “A Letter to My Nephew.” Written to my father, it helped him navigate through a toxic and racist country that, across generations, attempted to hide its evils like an inappropriate affair. It breathed possibility into the so-called American dream, for which Black people were given a commercial but never the product.Uncle James inspired me to write my own essay, to my fellow Black chefs, with hope that this provides an understanding of where our people originate from and where we are destined to go.Dear Chef:I wrestled with writing this letter. I worried that if I stirred up the pot of inequities that exist in the hospitality industry, it might affect my comfortable position within my chosen profession. Roughly 80 percent of the people that patronize my brand don’t look like me, so being vocal might help my colleagues but hinder my own financial well-being. But I feel my moral currency is much more valuable.

My journey began at seventeen, when I served in the U.S. Navy in intelligence communications. I fought in the Gulf War across two operations, Desert Shield and Desert Storm, for freedom and equality for a country that was supposed to protect me. But history will show when service members say they fought for this country, they fought for white ideology.

My culinary journey spans twenty-five years of trials and triumphs, but mostly anguish. Like many chefs, I started cooking with my mother, an amazing cook from the land of Gullah cuisine. And although creating delectable dishes brewed in my soul, I couldn’t turn my passion into profit.As you fight for position, it becomes clear: The deck is stacked against you and across generations. As African Americans, we were stripped of dignity; our resolve was diluted and our memories of regal legacy removed. Emotional holes were created, leaving us hungry and in survival mode. Seeds of self-hatred were planted.Chef, your struggle for equity in this industry is a direct legacy of slavery, and the classic “BS” quote about pulling yourself up by your bootstraps is self-reliance rhetoric steeped in white privilege. It’s hard to pull yourself up by bootstraps when barefooted.The wounds of slavery still bleed in U.S. soil, and the gritty truth of who we are has fallen on deaf ears. We tilled the land. Planted seeds. Harvested fruit and vegetables. Milked the cows and butchered livestock. Pickled the vegetables for winter and cured the meats. We fished the waters. Cooked the food while setting the table. We served the food and cleaned the dishes.Our people did all these tasks, by force and for free. The United States’ hospitality industry was created off our backs. And after 400-plus years of being the creators of a multi-billion-dollar industry, we still don’t have a seat at the table. Are we now the modern-day slave, when our contributions to this industry are invisible and the fruits of our ancestors’ labors are denied to us? Those that find this question extreme have not walked a day in my clogs.

In 1999, I used my military benefits to enroll into culinary arts at Stratford University. I knew my destiny was ahead and it was imperative to commit to this industry.My ancestors experienced treachery but endured, survived, and moved forward. We must imagine and cultivate this Afrofuturistic undertaking. We must create spaces where African Americans can prosper and minimize the oppression that diminishes our power.I call the artistry of cooking my true love, but I question if she loves us Black chefs back. All that we continue to give her makes me ask if this love is mutual or if the scales of justice have failed to tip in our favor.A 2020 study by the Castell Project found that while Black people make up nearly 18 percent of the hospitality industry, of which food and beverage service is the largest segment, they hold less than 1 percent of the CEO jobs within the industry.The lack of Black chef representation is because the top of the corporate structure doesn’t understand the value of our contributions. I know this conversation can get uncomfortable when we peel back the layers of diversity, equity, and inclusion. The implicit biases— such as assuming Black chefs can cook only soul food—speaks to how we’ve been relegated to a single, creative dimension.To change this picture, we must demand diversity from the break room to the boardroom. Focused transformation assumes expanding corporate executive diversity, allowing equity to trickle down. I use the word trickle deliberately. This low and slow process requires handholding and soul-searching.Here’s a softball question: Can you name a Black chef? If Marcus Samuelsson is your only answer, God help us. Yes, we have had a Black President and now a female Vice President of color, but that doesn’t mean systemic racism is a thing of the past. Influences of Black political power must span greater, and the influence of our chefs must continue to grow.Key questions remain unanswered: Why are we still considered lesser than white people? Why must we work twice as hard, only to be passed over? Feelings of discontent emerge for the industry we pledged allegiance to when it doesn’t recognize our contributions. I want to challenge this relationship. Black America is owed something that America has for too long held back: respect.Reparations begin when the United States acknowledges its greatest sin: building a country on the backs of human bondage. Instead, we are prolonging breakage, driving deeper wounds atop legacy scar tissue. Our racial divide will impact future generations.I want to enlighten you about the discrimination in culinary schools, which lure future Black and brown chefs with the possibility of being the next star.The Food Network is one of the key players in the rise of the celebrity chef. While it’s praiseworthy for transforming a blue-collar job to something that enjoys white-collar treatment, the culinary institutions that benefit from this programming are predominately white.For more than twenty years, these institutions herded students of color through workforce development grants accompanied by subpar education. Widespread educator teams are underqualified, lacking passion and commitment to their craft. How do we expect students to have a fighting chance to compete?It would be wrong to paint all culinary schools negatively. By no means am I taking that stand. But you must be informed about the schools’ credentials and influence. Ask questions! What relationships do they have within the industry, including internships and externships? What is their job placement percentage? What position in the industry will you be suitably trained for? Who are the previous graduates that have been major industry influences? Make sure the answers are satisfactory. What does this institution have to offer you?We must stand together to ensure our hospitality educational institutions and the overall industry have a double bottom line—profit along with purpose. We must be resolute in helping combat the power structure that continues to plague our rise. We must demand a seat at the table and have a commanding voice that’s heard.Forging a unified front, we must understand the difficulty of being our brothers’ or sisters’ keeper. Why do we have disdain when our fellow Black chef is celebrated? Why them and not me? Having been in this industry for decades, I still grapple with why my fellow Black chefs rarely connected, helped to establish, or brought me opportunities. We must abandon our Black envy, improve elevation, and celebrate one another.We must strive for excellence. We must promote organizations that uplift and support Black people on center stage, as well as those committed to helping bridge the equity gap for industry members.It’s time for us to reclaim what was taken from us. We must gather our culinary tribe to effectively move this industry forward. The power is in the people. It is imperative that we pronounce our presence.Hercules Posey, an African American enslaved by the family of George Washington, served as that family’s head chef. Thomas Jefferson’s head chef, James Hemings, was the first American to train in France, adding flavors to our rich culture. Leah Chase, an African American chef, author, and television personality from New Orleans, became known as the Queen of Creole Cuisine. Chase received a James Beard Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award in 2016.These few are not enough. Join me in growing these names committed to culinary excellence, owning their brand, and knowing their worth.When we ask, “Name me a Black chef?” it should be your name we celebrate. It is you who has helped create a space for authentic, unapologetic best versions of what we can achieve. God bless you, Chef, and Godspeed.

Malcolm James Mitchell

Malcolm James Mitchell (malcolm-mitchell.com) is an accomplished chef, author, restaurant consultant, and television personality. He wishes to thank Niquelle L. Cotton of Q-factor Consulting for her editorial assistance.